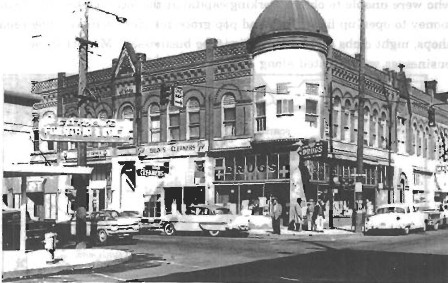

North Williams Avenue with the Citizens' Fountain Lunch North Williams Avenue with the Citizens' Fountain Lunch |

By Lisa Loving Of The Skanner News

If ever the City of Portland wanted a model for a 20-minute urban neighborhood, Albina in 1956 was it.

Until city leaders opted to bulldoze it for "urban renewal."

Doctors' offices, bike shops, groceries, churches and an ice cream store. Manufacturing, greenspace, boutiques, salons and plenty of affordable housing.

The current debate about North Williams Avenue – once the heart of Albina's business district -- is only the latest chapter in a long story of development and redevelopment.

The Skanner News this week unveils our special tribute to the families who lost their homes and businesses over the years with this interactive Google map feature listing every business along North Williams Avenue in 1956 – including Dr. DeNorval Unthank's medical office -- paired with a street view of what is on North Williams now.

(Go to "Portland, Or., Gentrification Map: The North Williams Avenue That Was – 1956") Click on the "+" icon in the map's upper left corner and wait for the street-level view to load.

We left out private homes, of which there were many, to link our historical account of gentrification there on the impact of city policies on small businesses.

A Fateful Era

Mrs. Power in front of the Power's family grocery store, 1956 Mrs. Power in front of the Power's family grocery store, 1956 |

For Albina, the district which included the city's traditionally African American neighborhoods, 1956 represents the height of home ownership, business success and tightly-bound family connections.

It was a watershed year for other reasons as well: Terry Doyle Schrunk won election to mayor on an urban renewal platform, firmly laying the track for creation of the Portland Development Commission two years later – the arm of city government which carried out wide-scale demolition of neighborhoods for decades to come.

It was the year voters approved construction of Memorial Coliseum in the Eliot neighborhood, ensuring the tear-down of more than 450 homes and businesses.

It was also the year federal officials approved highway construction funds that would pave Interstates 5 and 99 right through hundreds of homes and storefronts, destroying more than 1,100 housing units in South Albina.

By 1962, the PDC's "Central Albina Study" earmarked the area as "beyond rehabilitation." The city document "History of Portland's African American Community (1805-to the Present)," quotes the study:

"Clearly, urban renewal, largely clearance, appears to be the only solution to, not only blight that presently exists in central Albina, but also to avoid the spread of that blight to other surrounding areas."

First AME Zion Church First AME Zion Church |

The Polk's Guide for that year shows scores of vacant properties along North Williams.

When it came time for local officials to win grant funds from the federal government to expand Emanuel Hospital, the 1966 grant application read, in part: "There is little doubt that the greatest concentration of Portland's urban blight can be found in the Albina area encompassing the Emanuel Hospital. This area contains the highest concentration of low-income families and experiences the highest incidence rate of crime in the City of Portland. Approximately 75 percent to 80 percent of Portland's Negro population live within the area. The area contains a high percentage of substandard housing and a high rate of unemployment."

Portland won the grant, and demolition of buildings began in the late 1960s. Within a few years the federal money ran out for Emanuel Hospital expansion – after the demolition was complete.

Cause and Effect

Contrary to popular belief, ghetto neighborhoods are not a chance occurrence, nor are they the natural evolution of "old housing stock" that hasn't been properly maintained by its owners.

In her ground-breaking study, "Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000," Portland State Urban Studies Adjunct Professor Karen J. Gibson detailed how municipal development policies, coupled with racism in the real estate and banking industries, left Portland's Black community segregated, ghettoized and, finally, scattered.

In her ground-breaking study, "Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000," Portland State Urban Studies Adjunct Professor Karen J. Gibson detailed how municipal development policies, coupled with racism in the real estate and banking industries, left Portland's Black community segregated, ghettoized and, finally, scattered.

And the same thing happened all over the country.

"In cities across the nation, urban power brokers, with the help of the federal government, eagerly engaged in central-city revitalization after World War II," Gibson wrote in "Bleeding Albina." "Luxury apartments, convention centers, sports arenas, hospitals, universities, and freeways were the land uses that reclaimed space occupied by relatively powerless residents in central cities, whether in immigrant White ethnic, Black, or skid row neighborhoods."

The study includes quotes from oral histories gathered decades earlier about the region's history.

"Oregon was a Klan state—it was as prejudiced as South Carolina, so there was very little difference other than geographic difference," said early civil rights leader Otto Rutherford, in 1978.

Gibson says her historical research uncovered a memo penned by a PDC official reassuring the federal Housing and Urban Development department about racial concerns in tearing out the homes and businesses for Emanuel Hospital expansion in the early 70s.

"The whole transition has been racial," Gibson told The Skanner News this week. "People paid taxes in Albina – what did they get for their taxes?"

In 1956 area banks could legally deny loans to any Black customer who applied, making the NAACP Credit Union -- one of North Williams' lost storefronts – a particularly poignant marker.

"Race was used, and the stagnation and redlining was racially based," Gibson said.

"The whole thing has to do with race, and it has to do with real estate.

"White privilege means something – it means a difference in wealth and the fact that you could just come in and take over the boulevard," Gibson said.

Housing Destroyed Despite Promises

Emanuel Hospital protest, early 1970s Emanuel Hospital protest, early 1970s |

When the PDC, city of Portland officials and the federal Model Cities program rolled out the endgame on tearing down Albina homes and businesses for Emanuel's expansion in 1971, many local residents did not realize the plans had been laid years before, according to "History of Portland's African American Community."

The Emanuel Displaced Person's Association was founded by Mrs. Leo Warren in 1970 after locals "were abruptly confronted with the expansion plans." The city required residents to move out within 90 days, offering homeowners a maximum $15,000 payment and renters a maximum $4,000.

A much-hyped agreement signed by the hospital, the PDC and the Housing Authority of Portland mandated they would use "maximum energy and enthusiasm" in replacing the lost housing within the Eliot neighborhood – none of which happened, according to "History."

Mrs. Warren is quoted in the history document from an interview with the Portland Observer:

"Didn't they have a long-range plan? After all, if your life's investment was smashed to splinters by a bulldozer to make room for a hospital, you could at least feel decent and perhaps tolerable about it; but to have it all done for nothing? Well, what is there to feel?"

Urban Planning Now

Albina resident Lisa Manning was also quoted in "Bleeding Albina."

"It used to be that living 'far out' was 15th and Fremont. Now it's 185th and Fremont. A lot of people leave the neighborhood  because they feel they're leaving something that's not theirs anymore anyway. It will never be that way again. There's a lot of sadness. For a lot of us, it's just too hard to stay and watch your history erased progressively over time. There are just too many ghosts," Manning said.

because they feel they're leaving something that's not theirs anymore anyway. It will never be that way again. There's a lot of sadness. For a lot of us, it's just too hard to stay and watch your history erased progressively over time. There are just too many ghosts," Manning said.

Gibson says anyone weighing in on the current citizens' advisory process for North Williams Avenue transportation safety should take a moment and look at past plans. She singled out the 1993 Albina Community Plan drafted under the leadership of then-Portland Planning Bureau Commissioner-in-charge Charlie Hales, who is now running for mayor.

"African Americans were heavily involved in the Albina plan," she said. "The Planning Bureau should probably provide us with an update.

"There have been other plans, but for me the key for any of the plans is how well are they carried out? We should evaluate how well some of those plans play out in the end."

(Would you like to see a residential map of the homes destroyed along North Williams? Would you like to see more interactive map features on other parts of town? Post a reader comment after this story on your areas of historical interest that touch on the old Albina District and your suggestions may lead to more related coverage.)

Read "History of Portland's African American Community"

Read "Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment"